Butterflies on Mount Sutro in 2020

Editor’s Note: Liam O’Brien started conducting twice-monthly butterfly surveys on Mount Sutro in 2020 as part of our wildlife monitoring for U.C.S.F.’s new Vegetation Management Plan, which was the subject of our previous blog post.

By Liam O’Brien

Saturday, February 13, 2021 was a glorious day. The sun was perfect, the Castro was full of people on the streets (like the old, pre-Covid days ) and low wind cemented in my mind that I needed to visit the summit of Mount Sutro.

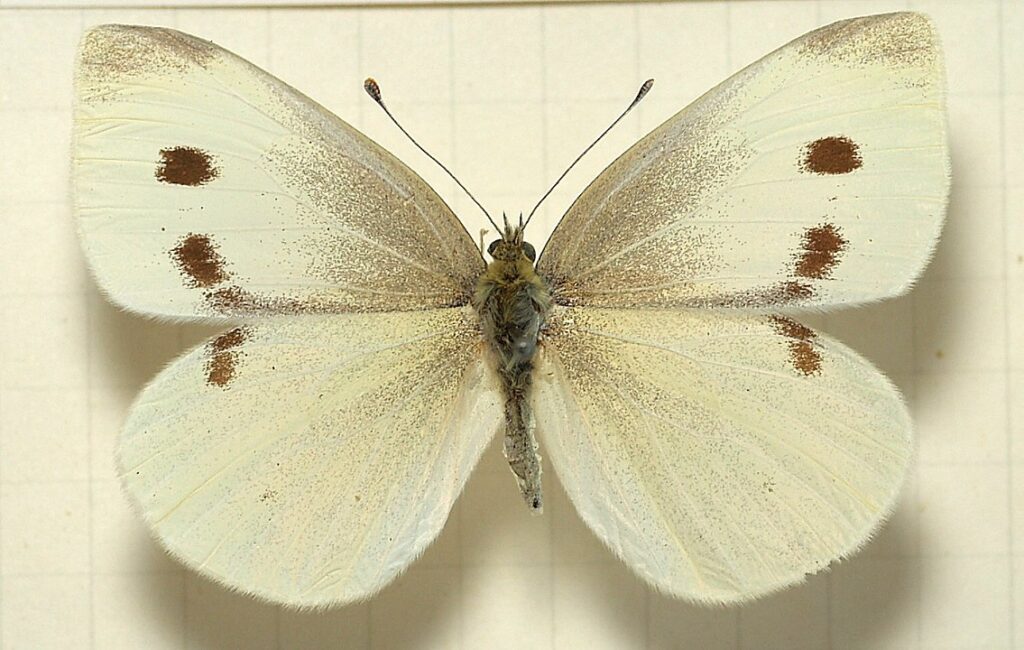

After an arduous hike up, I entered old Nike Road through the dappled sunlight of the eucalyptus forest. It was too early for the Western Tiger butterflies I’d seen here last year. But there dancing above the nasturtiums was a lone Cabbage White (Piers rapae)—a full month earlier than the first one I’d seen here in 2020.

There is an annual contest held by the great butterfly professor Arthur Shapiro in Davis, California. He buys a beer for any of his students who can catch and verify the first Cabbage White of the season. A few days before my Mount Sutro visit, the first one of 2021 had been caught outside Sacramento city limits. This San Francisco sighting was my first butterfly of the new year. Folks dismiss the Cabbage White as one of those “rat” species and a rather generic butterfly. But I think it’s the perfect species to pause on in this write-up on before the flashier ones start to show up in springtime.

I’m going to now shift things to reviewing my 2020 surveys, gleaned from the annual report I turned into Golden Gate Bird Alliance in January.

It’s been wonderful to return to this little Eden month after month. I’ve gotten to watch the seasonality change, with different types of birds and bees passing through and the flowers—so incredibly important to butterflies—going through their life cycles. Ultimately 2020 revealed 20 species of butterflies that dropped into the summit of Sutro over the course of the year.

When I created the Butterflies of San Francisco pamphlet in 2010 for Nature in the City, I concluded that we had approximately 34 breeding species within our county. This would give Mount Sutro a little less than 2/3 of the known species in town.

The summit of Sutro has a couple of things going for it when it comes to butterfly presence. The vast array of native plantings creates a balanced stew of possibilities for wildlife. Many times I didn’t just see a butterfly up here but saw it on or near its host plant—the plant or family of plants where it lays eggs. I found Echo Blues dancing mid-canopy around the blooming buckeye tree or Ceanothus bush, Field Crescents patrolling the asters for mates, and Acmon Blues weaving through the coastal buckwheat.

Another draw for butterflies is the sheer topography of Sutro, as I’ve discussed in prior blog posts. The phenomenon of hill-topping is on full display daily with Anise Swallowtails and Gray Hairstreaks.

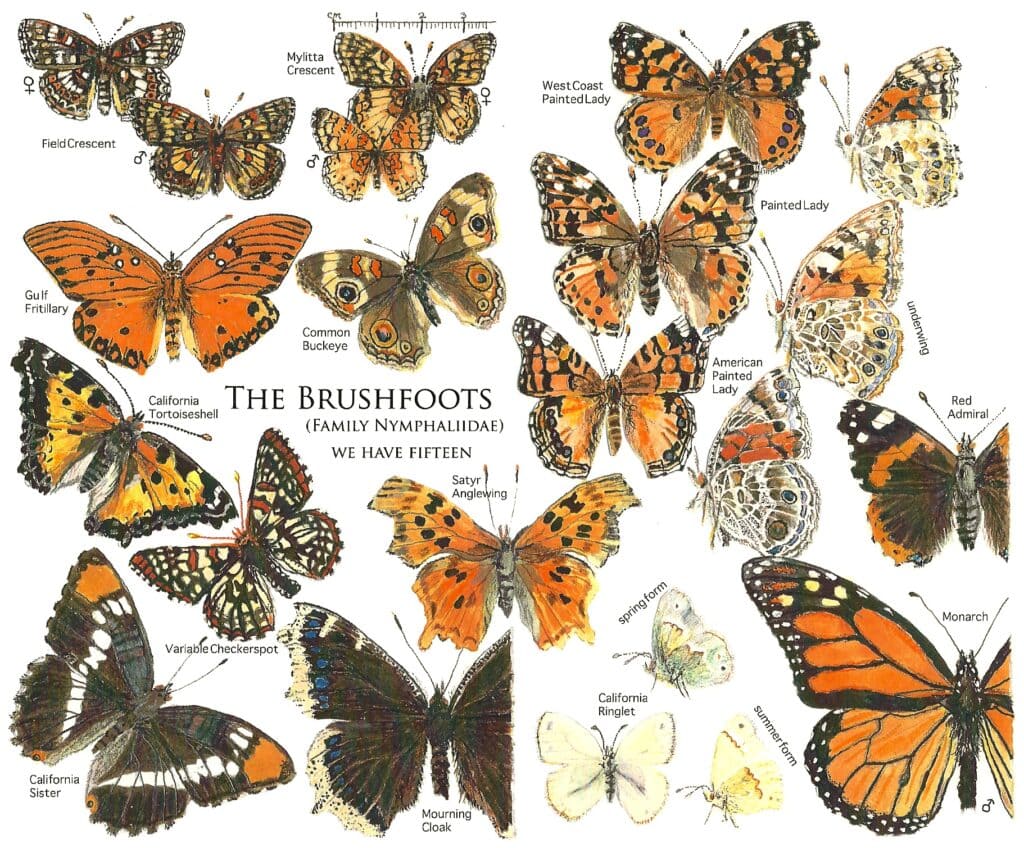

The forest of eucalyptus surrounding the hilltop garden does not, in my opinion, deter or pose much of a barrier for some of the larger San Francisco species such as Western Tiger, Red Admiral, and Mourning Cloak. But it doubtless has a great deal to do with some of the other known species I did not see: Mylitta’s Crescent, Western Pygmy, and Sandhill Skipper.

Medium-sized butterflies—primarily the Brushfoots/Nymphalidae family—had a solid showing, making up at least half of all butterfly species observed (10 in total ). Singletons, where I saw only one of each species, numbered seven. I saw only one Pale Tiger, Grey Hairstreak, Mourning Cloak, Variable Checkerspot, American Painted Lady, California Tortoiseshell, and Fiery Skipper.

The Rotary Garden/Open Space on the summit of Mount Sutro is basically a human-made botanical garden perched on top of a mountain. The drip forest from the eucalyptus makes all of the bushes much more robust than they would be in an exposed coastal-scrub habitat. This provides nourishment for larvae beyond their normal cycle.

There is an old adage that I’ve never been a big fan of: “Plant them and they will come.” It seems too pat. But after this year on Mount Sutro, I have to reconsider. Just how did those Common Buckeyes find this place? Did the Field Crescents come in on plants as eggs? I’m grateful that Golden Gate Bird Alliance has extended my surveying contract for a few more years. There are many more questions we still have to answer.

Liam O’Brien is a San Francisco lepidopterist who has created projects including The Green Hairstreak Corridor and Tigers on Market Street for Nature in the City and Operation Checkerspot for the Presidio Trust. He received the 2014 Environmental Educator Award from Bay Nature Magazine. His blog, The Flying Pansy, can be found on Bay Nature‘s web site. Look for his first book by Heyday Press in 2023. You can also follow Liam on Instagram at @ROBBER_FLY. Got questions for Liam? Email him at liammail56@hotmail.com.