Palm oil – not an environmentally friendly food or fuel

By Bob Lewis

I was fortunate to visit Malaysia in 2015, both Borneo and the peninsula, as well as a few islands of Indonesia. The forests there are spectacular, some of the most diverse and rich in terms of all sorts of animal and plant life. Primates included Orangutan (critically endangered), Western Tarsier, Proboscis Monkey and many others; the butterflies were spectacular, and the birdlife was exciting to see. There was even a new family for me to photograph: the endemic Bornean Bristlehead (classified as near-threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature)!

We visited an IBA (Important Bird Area) in Borneo’s Danum Valley, a lush jungle with treetop walkways; Fraser Hill, north of Kuala Lumpur; Taman Nagara, Malaysia’s oldest jungle National Park; as well as many other places. They were all full of wonderful sights like the Daird’s and Scarlet-rumped Trogons (both near-threatened), White-crowned Hornbill (near-threatened), Bornean Wren-babbler (vulnerable) and Black & Yellow Broadbill (near-threatened).

Unfortunately, these wonderful places are becoming oases in the middle of palm “deserts,” monocultures that are not suitable habitat for any of the birds and mammals that inhabit the forests. And that explains why so many creatures are now considered threatened or endangered by the IUCN. When I got home, I started to learn more about the palm oil industry.

Throughout Southeast Asia, and especially in Malaysia and Indonesia, tropical forests are being lumbered and burned, and palm oil plantations are taking their place. Everywhere I looked outside the parks, the impact of the palm oil industry was clear to see – either already-producing plantations consisting of miles of palm trees in perfect lines, or evidence of future plantations, such as logging residue where forests had been, or smoke pillars from burning, trenched peat that remained after the forest was logged.

According to the IUCN, Indonesia’s birdlife includes 429 endemic species, of which 82 are threatened. The threat continues to grow as the forest is destroyed. In the Fall 2016 issue of Audubon magazine, Jocelyn C. Zuckerman discussed the problems of illegal clearing, burning and poaching. Much of the Indonesian lowlands is tropical peatland: On Sumatra it can reach a depth of 25 feet, and contains much more biomass than the covering forests. When the land is cleared and burned, prior to canalization and palm planting, the carbon in the peat is released into the air. So in addition to destroying some of the most biologically diverse forests in the world, the palm oil industry contributes greatly to CO2 emissions.

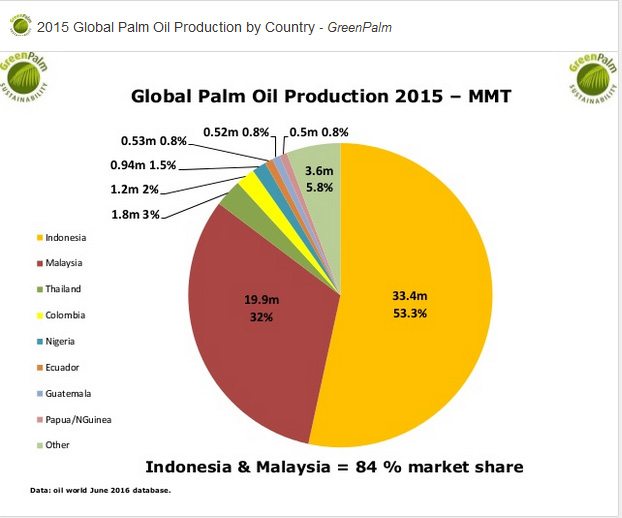

According to Zuckerman, Indonesia ranks fifth in the world in greenhouse gas emissions, and 85 percent of its emissions are due to forest clearing and burning. Indonesia’s production of palm oil is growing sharply, from 28.4 metric tons in 2013 to 33.5 tons in 2014 and a projected 40 metric tons in 2020. Palm oil accounted for 11 percent of Indonesia’s export income in 2014. The country has a strategy of increasing the market for palm oil by converting it to biodiesel fuel, and a number of companies are building refineries for this purpose. They include Cargill (300,000 tons per annum or TPA in Rotterdam), Astra Agro Lestari Terbuka (150,000 TPA), Wilmar International (25 refineries across Indonesia) and Musim Mas Group.

Although the numbers are disputed, indications are that European use of palm oil in biodiesel increased from 8–10 percent of EU palm oil imports in 2010 to 30–45 percent in 2014. In 2012, Indonesia surpassed Brazil to become the fastest forest-clearing nation in the world. Biodiesel from palm oil leads to destruction of forests and burning of peat lands, both of which increase CO2, and destruction of some of the most biologically diverse forests in the world. It is NOT environmentally friendly.

Greenpeace and Rainforest Action Network have been trying to raise global awareness regarding this problem for a number of years. After much effort, in 2014 a group of large palm oil buyers pledged to end deforestation, and to purchase their palm oil in an environmentally responsible way. In 2015, after serious fires in Indonesia resulted in region-wide air pollution and drew public attention to the problem of forest clearing, Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo announced ambitious new plans to mitigate against future fires by protecting Indonesia’s peatlands. This included a new Peat Restoration Agency tasked with enforcing a moratorium on further peatland development, as well as the restoration of land burned during the 2015 fires.

This sounds positive for Indonesian forests. In December 2015, however, Greenpeace contacted 14 major palm oil consumers to see how things were going. Results were not very positive. You can see Greenpeace’s evaluation at this scorecard, and Rainforest Action Network’s here. In summary, Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson, Kraft-Heinz and Pepsi have made little or no progress. On the positive side, Ferrero and Nestlé have made significant progress.

Stopping forest clearing NOW in both countries is critically important to the health of animal and bird life in Southeast Asia, as well as to our global health. Animals at risk include Sumatran Rhinos, tigers and elephants, as well as our close relative, the Orangutan.

Birds are suffering not only from habitat loss and fragmentation, but also from increased poaching, made possible by new roads supporting the palm oil industry. Hornbills, critical to forest health because they distribute nuts and seeds, are especially at risk because the casque of the Helmeted Hornbill is valued for traditional Chinese medicines and carved jewelry. Proceeds from a single casque can feed three families for a month. IUCN raised the level of concern for this bird from near-threatened to critically endangered between 2012 and 2015. Meanwhile, during this time 2,400 Rhinoceros Hornbills are estimated to have been killed, and only 3,000 remain in Indonesia. In Sumatra, more than 75 percent of the 102 lowland-forest-dependent bird species are now considered globally threatened.

There is an industry organization called Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) that claims to set standards for sustainable production, but it continues to permit forest clearing. Many palm oil buyers like Proctor & Gamble promise to follow RSPO standards, but this doesn’t insure that the suppliers have stopped clearing new land. P&G has committed to reach a no-clearing purchasing plan by 2020, and has requested suppliers to develop a strategy by end of 2016 to reach this goal. But clearing land continues in Indonesia. Up to 80 percent of land clearing is said to be done illegally, so passing laws is insufficient deterrent. Driving down the value of palm oil until the industry organization agrees to a no-clearing policy is an approach that might be more effective.

Over 50 percent of products found on supermarket shelves have been found to contain palm oil or its derivatives. Consumers can do two things – avoid products with palm oil, or if that’s not possible, purchase from Nestlé and avoid Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson and Pepsi. And tell them why!

Continued pressure on the governments of Indonesia and Malaysia through NGO’s like Greenpeace and Rainforest Action Network is probably the most effective route to converting the industry to a truly sustainable, non-forest destroying entity. Please support them.

Bob Lewis was trained as a chemist, and worked for Chevron in Richmond and Europe for 33 years. He has taught birding classes for 23 years, and has been an addicted birder, photographer and traveler for almost ever. He has seen 4,600 of the world’s 10,000 bird species, and hopes to see many more! Bob served on Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s board for 11 years, and was chair of the Adult Education Committee during much of that time. He won ABA’s Chandler Robbins Award for Education and Conservation in 2016.