Birding While Black

Editor’s Note: Some people go birding to escape from the stresses of daily life. For birders of color, those stresses often continue into the field. This timely and compelling essay is excerpted with permission from J. Drew Lanham’s new book, THE HOME PLACE: MEMOIRS OF A COLORED MAN’S LOVE AFFAIR WITH NATURE.

By J. Drew Lanham

It’s only 9:06 a.m. and I think I might get hanged today.

* * * *

The job I volunteered for was to record every bird I could see or hear in a three-minute interval. I am supposed to do that fifty times. Look, listen, and list for three minutes. Get in the car. Drive a half mile. Stop. Get out. Look, listen, and list again. It’s a routine thousands of volunteers have followed during springs and summers all across North America since 1966. The data is critical for ornithologists to understand how breeding birds are faring across the continent.

Up until now the going has been fun and easy, more leisurely than almost any “work” anyone could imagine. But here I am, on stop number thirty-two of the Laurel Falls (Tennessee) Breeding Bird Survey route: a large black man in one of the whitest places in the state, sitting on the side of the road with binoculars pointed toward a house with the Confederate flag proudly displayed. Rumbling trucks passing by, a honking horn or two, and curious double takes are infrequent but still distract me from the task at hand. Maybe there’s some special posthumous award given for dying in the line of duty on a Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) route—perhaps a roadside plaque honoring my bird-censusing skills.

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book

The Home Place, J. Drew Lanham’s new book

My mind plays horrific scenes of an old black-and-white photograph I’ve seen before—gleeful throngs at a lynching party. Pale faces glow grimly in evil light. A little girl smiles broadly. The pendulant, black-skinned guest of dishonor swings anonymously, grotesquely, lifelessly. I can hear Billie Holiday’s voice.

The mountain morning, which started out cool, is rapidly heating into the June swoon. I grip the clipboard tighter with sweaty hands, ignoring as best I can the stars and bars flapping menacingly in the yard across the road. The next three minutes will seem much longer.

On mornings like this I sometimes question why I choose to do such things. Was I crazy to take this route, up here, so far away from anything?…

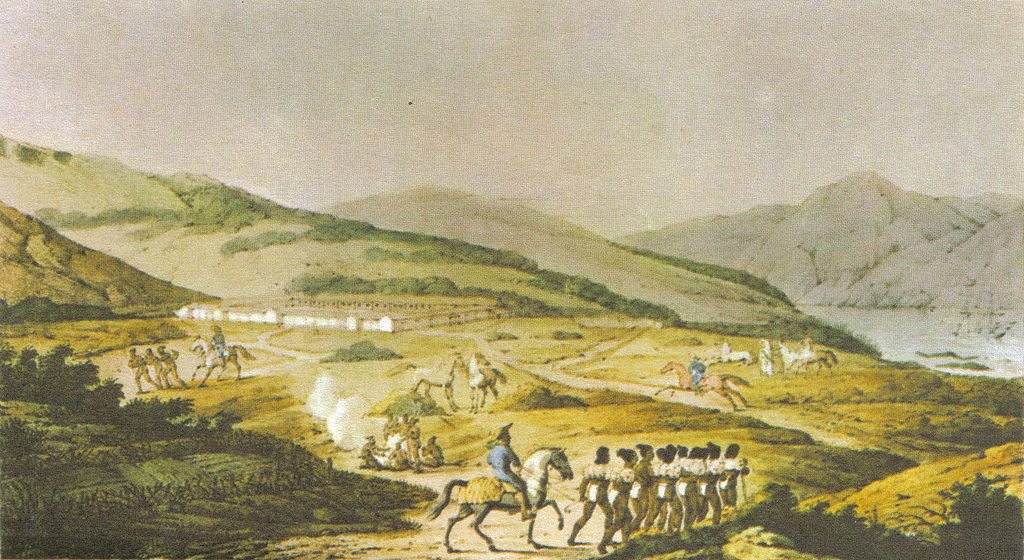

The Presidio in 1817 by Louis Choris

The Presidio in 1817 by Louis Choris

Planes lined up at Crissy Field in the 1920s / Wikipedia

Planes lined up at Crissy Field in the 1920s / Wikipedia

Crissy Lagoon today / Photo by David Assmann

Crissy Lagoon today / Photo by David Assmann