On Naming Individual Birds

By Ryan Nakano

When I bought my first car I named it Lorelai, after Lorelai Gilmore from the show Girlmore Girls. Growing up with beagles, my family had Elsa, and then Buddy. My cat has many names, the primary of which is Eevee, after the Pokemon, although this is disputed by my girlfriend who named our cat after her aunt and did in fact sign the paperwork. The Black Phoebe I see almost every morning at the rose garden is simply Phoebe.

The point is, naming is both fascinating and complicated.

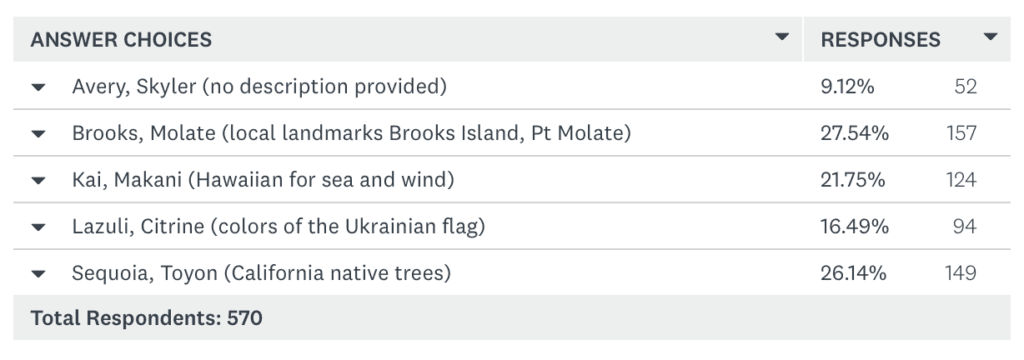

Last week Golden Gate Bird Alliance finished up a naming process for two new Osprey chicks. After receiving 570 responses to a choice of five pairs of potential names, it was decided that the chicks would be known as Brooks and Molate. Prior to this vote, we opened up for name suggestions and received 125 submissions. After participating in the process for submission review, I couldn’t help but think about the act of naming individual wild animals and the thought process behind what names we believe to be appropriate or representative of them.

In an article titled What’s in a Name?—Consequences of Naming Non-Human Animals author Sune Borkfelt addresses the necessity of naming as a communication tool.

“Indeed, it is naming something that enables us to communicate about it in specific terms, whether the object named is human or non-human, animate or inanimate.”

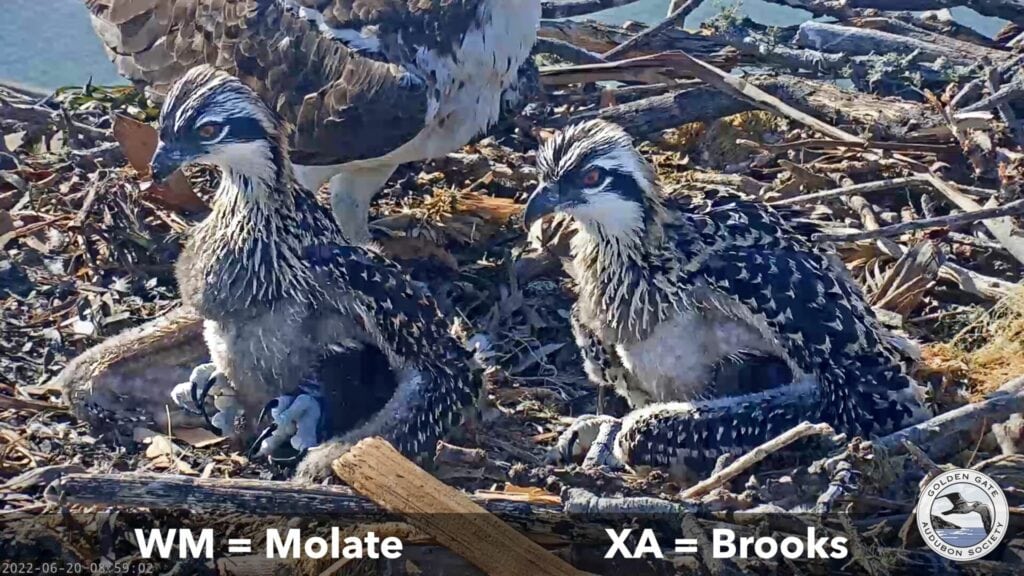

Now, instead of sharing that chick A and chick B are starting to become easier to tell apart, I can say that Molate has a broader dark stripe on the back of their head, while Brooks’ head is lighter in color. But why Brooks and Molate?

Named after two important bird areas local to the Bay Area, Brooks Island and Point Molate, it would appear that these birds now represent a reminder to continue preservation and restoration efforts of our shared natural environment.

Borkfelt goes on to note, “A name is a representation and can therefore potentially carry all the values, ideas, perceptions and conceptions carried by representations and have the array of potential consequences, which can ensue from representation.”

Under this premise, these two new chicks now intentionally or unintentionally become the mascots for local bird habitat and the ongoing efforts to preserve such spaces. (Which, all things considered, doesn’t seem like a bad thing!)

Of course, Brooks Island itself was onced named after something, limited research concludes that it is an eponym to an unknown person from the past. Point Molate traces its naming history back to 1826, where the spanish word ‘Moleta’, referring to a kind of conical grinding stone with a similar appearance to the island known as Red Rock, was misspelled as Molate. It follows that the two new chicks are secondarily named after an unknown human being and a misspelled tool.

What’s maybe even more interesting than the final names for these individual osprey chicks, was seeing the other submissions. After reviewing all 125 of them, there were some clear categories that stood out that seemed to inform people’s decision on what to name these birds.

In no particular order I’ve listed the categories below, names based on…

Nature, Individual people (eponyms), Habitat/urban surroundings, Parent’s attributes, Deities, Ideals/values, Human-made things and accomplishments, Planets, Important bird areas, Local indigenous individuals and tribes, A country in need of support, Fictional birds, Food consumed, Behavior, Common name in another language, Local regions, The city of Richmond’s motto.

Within this short list, it becomes apparent that there is a wide variety of ways that people think about naming individual wild animals. Some of these naming categories—such as names based on behavior, food consumed, or habitat/urban surroundings—seem to suggest the want to choose names that say something about the birds themselves. Other naming categories such as names based on individual people, human-made things and accomplishments, or countries in need of support, feel like an attempt to use the birds to honor/acknowledge not birds but humans struggling and achieving to some end. The inclusion of deities, ideals/values, and even planets suggest that we can think of naming as an opportunity to create symbols to look to for guidance and solace.

So what? Why am I going on about naming a couple birds? Partially, I tend to nerd out about these kinds of things. But also, I believe naming can inform and shape our relationships toward the named for better or worse, and it’s worth exploring this within the context of conservation.

Within the same article by Sune Borkfelt, she states, “F. B. Welbourn, for instance, has written that ‘[b]y the act of naming the animals man recognized his responsibility towards them’ [10]. But of course this still presupposes an inherent powerlessness on behalf of the animals and therefore a natural inequality between humans and animals. Naming still signifies inequality and dominance, it is merely questioned what humans should do with this God-given power.”

This is the complicated part.

In another article Naming One That’s Wild: A Conservation Aid?, author Candice Gaukel Andrews notes that in Yellowstone National Park researchers purposefully do not give individual names to wolves to remind people that they are in fact wild animals, with some scientists worrying that naming them would lead to anthropomorphizing, leading to bias in research.

At the same time Andrews states “Other scientists argue, however, that wild animals and research animals that are named—and therefore seen as individuals—may be watched and tended more carefully, making them less stressed. They believe that’s better for the animals’ welfare as well as for scientific studies.”

I cannot help but think of Rosie and Richmond. Since 2017, we’ve hosted a nest cam on the historical Whirley Crane in Richmond, and garnered quite the following of viewers who enjoy observing the trials and tribulations of our local Osprey couple. I do get a sense that their names elevate them to a particular status in which we recognize them as individuals, making it easier for us humans to turn our empathy into potential action (see psychic numbing). At the same time, during this past nesting season, there were those who grew concerned over the conditions of Rosie and Richmond’s nest to the point of suggesting human intervention.

Part of me wonders if this concern grew out of the kind of presupposed powerlessness of nonhuman animals that Borkfelt mentioned, as if Rosie and Richmond would not be able to rebuild on their own. Fortunately, these birds have been making homes for a long time and seem to know what they’re doing without us, evidenced by the comforting nest in which Brooks and Molate now find themselves.

So, Brooks and Molate, let us hope your names bring us closer to our collective cause, and cause as little interference to your livelihood as possible. Live and let live, the unknown and the conical stone. May your names be a reminder of our responsibility and your autonomy as children of Richmond and Rosie, as wild and powerful beings with wings, talons and beaks.

Ryan Nakano is the Communications Associate for Golden Gate Bird Alliance. He also happens to be a poet, with a chapbook slated for publication in February 2023 with Nomadic Press.