New Bird Biology text is worth the wait

By Bob Lewis

In 2004, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology published the second edition of its Handbook of Bird Biology, a hefty volume of 11 chapters. It was in black and white, and Cornell offered a companion mail order course that seemed tempting to some at Golden Gate Bird Alliance, but at the same time appeared daunting. Della Dash suggested we assemble a study group, and I ended up leading two year-long groups of future bird biologists as we strove to qualify for our Cornell certifications. Those of us who succeeded became some of the 15,000 students from 65 countries who placed the certificate on our wall. In 2010 the book went out of print, and Cornell no longer supported the mail order class.

In 2013, after Jack Dumbacher had joined the GGBA Board, we embarked on a different approach to teaching bird ID and biology, offering our first Master Birding class at the California Academy of Sciences. Taught by Jack, Eddie Bartley and myself, with occasional guest lecturers, we are now completing our fourth year, each year with 20 registrants in the class. Although the class has evolved, much of it was based on Cornell’s Handbook.

A few weeks ago, the third edition arrived. Edited by Irby J. Lovette and John W. Fitzpatrick and published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., it is a thing of beauty.

With glossary and index it runs over 700 pages, and contains 15 chapters authored by 18 expert ornithologists. Five of the authors extensively revised their second edition contributions, while 13 contributed entirely new material. Many of the references in the new volume are post-2012, with some from 2016, covering recent advances in bird biology well. Also new to this edition are 1,150 color photographs, illustrations, and figures, adding much to the updated text. The second edition had a definite East Coast bias, with most examples coming from that area. The third edition approaches issues globally, picking illustrative examples from birdlife worldwide.

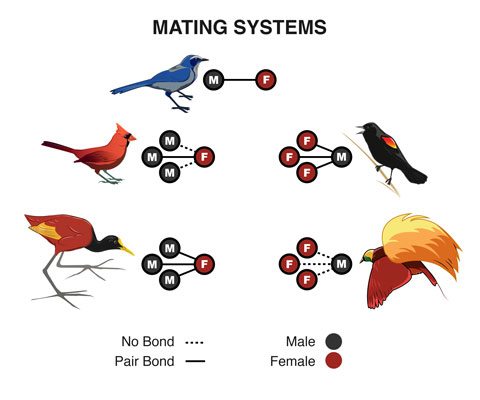

Chapters cover Bird Classification, Evolution, Flight, Anatomy, and Physiology. Behavioral aspects include Food and Foraging, Mating and Social Behavior, Song, Breeding Biology and Migration. And finally, Ecology of Bird Populations, Bird Communities and Bird Conservation complete the volume.

Looking at the chapter on Avian Diversity and Classification by Lovette, I was pleased to see clear definitions of sometimes complex concepts like Clade, Monophyletic group, and Species. After discussing methods for establishing avian relationships, including DNA studies, Lovette goes on to review early birds and theropod dinosaurs, Gondwana, and biogeographical realms and finishes with Winkler’s 2016 classification of avian orders and species. It’s 54 pages of fascinating stories of species distribution, relationships, and histories. I didn’t know that hummingbirds originated in the Old World (fossils from France) or that mousebirds, today restricted to Africa, once populated Europe and North America.

The last chapter on Bird Conservation is surely of most interest to conservation organizations like GGBA. Written by John W. Fitzpatrick and Amanda D. Rodewald of the Cornell Lab, the chapter asks why we should we be concerned with bird extinctions today if birds have been going extinct throughout their existence – and then provides the following answer:

“The wave of extinction currently underway is occurring at a pace and scale fully comparable to the five greatest extinction episodes in the earth’s history, but this sixth mass extinction is directly caused by human activities across the globe.”

Based on fossil deposits, the worldwide spread of modern Homo sapiens is claimed to have resulted in the extinction of about 8000 species of landbirds. The authors then go on to describe the disappearance of American megafauna 12,000 – 8,000 years ago, coincident with human arrival, and historical extinctions on islands as humans moved across the oceans.

Today IUCN (International Union of Conservation Networks) recognizes 11 categories of threats facing the world’s living species. In North America, “Invasive and other problem species and genes” and “biological resource use” (timber extraction) are the two most critical, with climate change being the third. Biodiversity hotspots, areas with a large proportion of endemic species are considered high priority for conservation action.

The U.S. West Coast is one such area. Birds are often used as indicator species, serving to call attention to overall ecological health of an area. The California Gnatcatcher is mentioned as a good indicator for coastal sage scrub in California. Flagship species, those that tend to draw collective attention to a conservation issue, include the Northern Spotted Owl.

In addressing solutions to extinction threats, attention is given to eliminating introduced mammals. New Zealand is the leader in these efforts, and has eliminated rats from dozens of islands, including 113-square-kilometer Campbell Island, permitting reintroduction of threatened endemic species there. The last section of this chapter talks about what each of us can do, covering backyard conservation, citizen science, environmental education, birding with youngsters, and encourages the reader to “never give up.” It might have been written for GGBA, now in its hundredth year of conservation leadership!

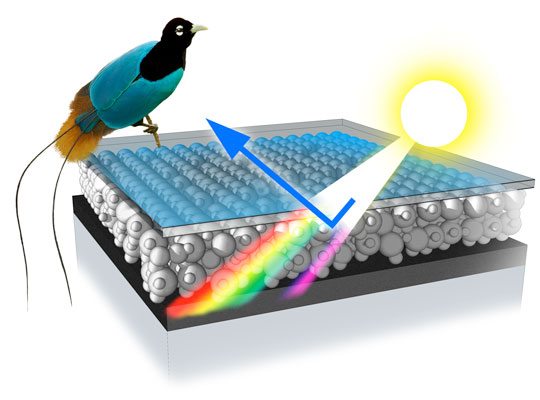

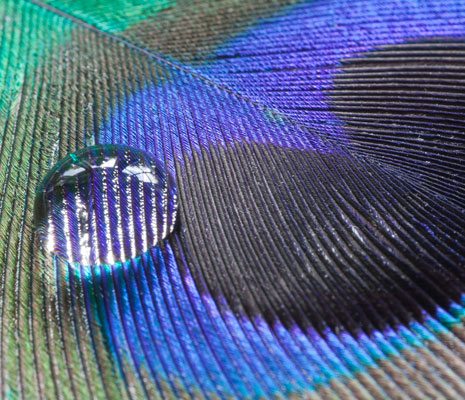

The third edition is complemented and supplemented by online materials on the Cornell website. The chapter on Feathers and Plumages has over 30 supplemental articles, videos and interactive features, helping to illustrate concepts and update science. And finally, Cornell is again offering an on-line course based on the Handbook, with lessons containing a short video and a series of short quizzes. Course instructors will provide an opportunity to have questions answered.

The course is offered for $239 and the Handbook is $135. Members of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology receive a significant discount.

Bob Lewis is a Golden Gate Bird Alliance birding instructor, field trip leader, and former board member, and is an award-winning bird photographer. Bob has been a birder for a long time, and travels the world to see rare and wonderful feathered creatures. Photographing them adds to the excitement. Bob’s bird photographs can be seen at http://www.flickr.com/