How fast can birds see?

By Jack Dumbacher

Decades ago, I recall being told that birds can see incredibly “fast” – mostly from bird keepers who said that AC lighting (which flickers at ~120 flashes per second) appears as a flashing strobe to birds. But when I started teaching Ornithology, I was never able to find any definitive published evidence that birds do actually see fast, or how fast, or even what this might mean for how birds see the world.

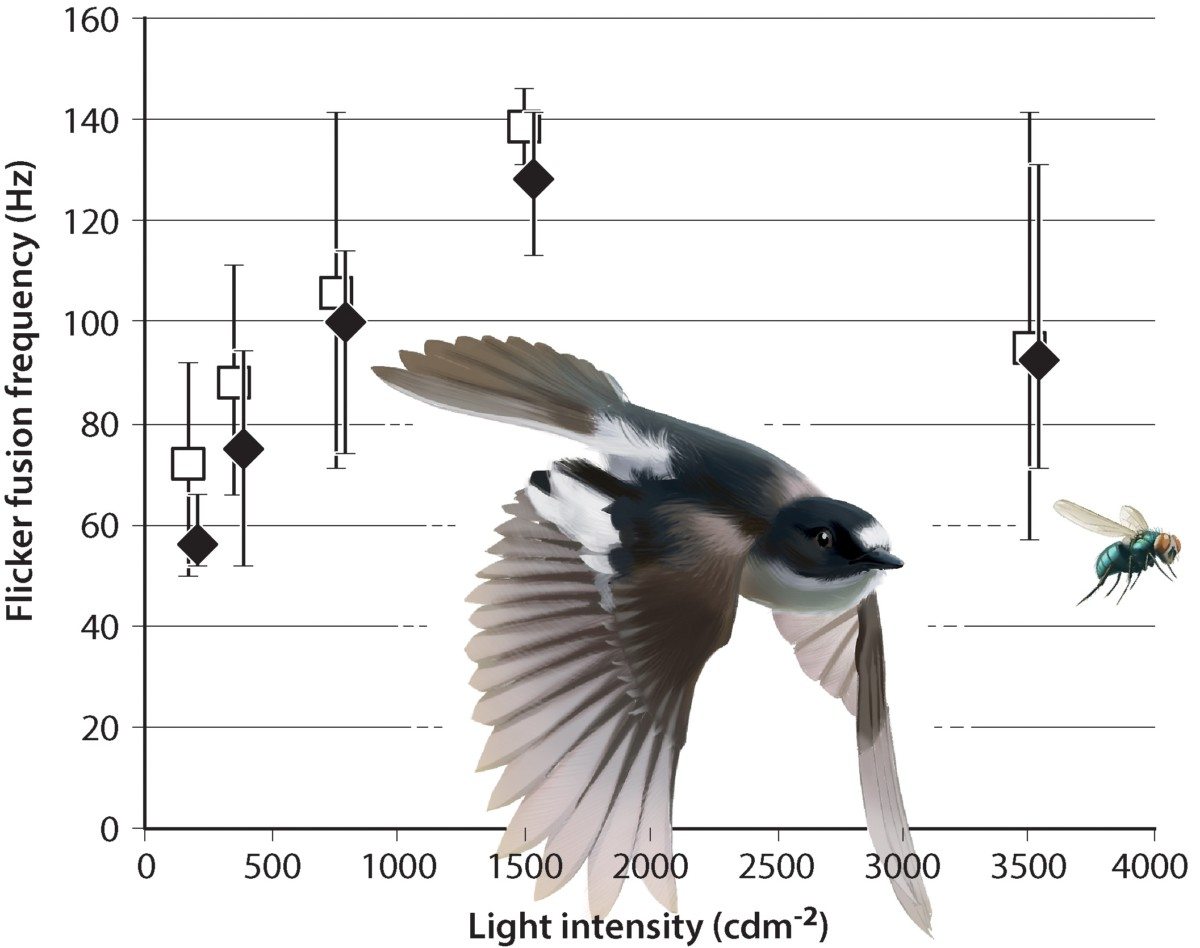

Now a recent study published by a Swedish team (Boström et al. 2016) nicely shows how fast birds can see. In fact, the Pied Flycatchers of Europe can detect flickering light and dark cycles up to 145 Hz (or flashes per second) – about 40 Hz faster than any other known vertebrate.

This is called the “critical flicker-fusion frequency,” or CFF – the frequency at which a flickering light begins to appear as a steady light.

In the eye, each light-sensitive cell has to react to light, send a signal to the brain, and then refresh to be ready to receive the next signal. As long as a flashing light is slow enough, each cell can keep up, and detect both the dark and light periods, and send a uniform signal to the brain. But once the flashing rate exceeds the critical flicker-fusion frequency, then some cells drop behind and get out of sync, and soon a synchronized “steady” signal is generated from the eye.

This is why the flickering motion on a TV screen or movie projector is viewed by humans as steady motion – because the light is flickering faster than our critical flicker fusion frequency.

To measure birds’ ability, they did some simple experiments with captive birds. Each bird could see two LED lights – one randomly chosen to flicker, and the other with a steady light. Then they simply trained captive birds to find a prize (a peanut for Blue Tits, or a mealworm for Collared Flycatchers) if they looked in a jar placed under the flashing light.

They waited until the birds were well trained and could get the treat at least four out of five times. Then they incrementally increased the speed of the flickering until the birds could no longer figure out which jar had the treat. This is an excellent test of birds’ visual acuity because it not only tested what the eye could theoretically do, but it tested how fast the actual eye plus nerves plus brains could truly detect the flickering – and provided direct evidence of how fast the birds actually do see.

They tested three songbird species – two old-world flycatchers (Collared and Pied Flycatchers) and Blue Tits, suggesting that this rapid vision is probably shared by most passerines, but probably much more widely among other birds.

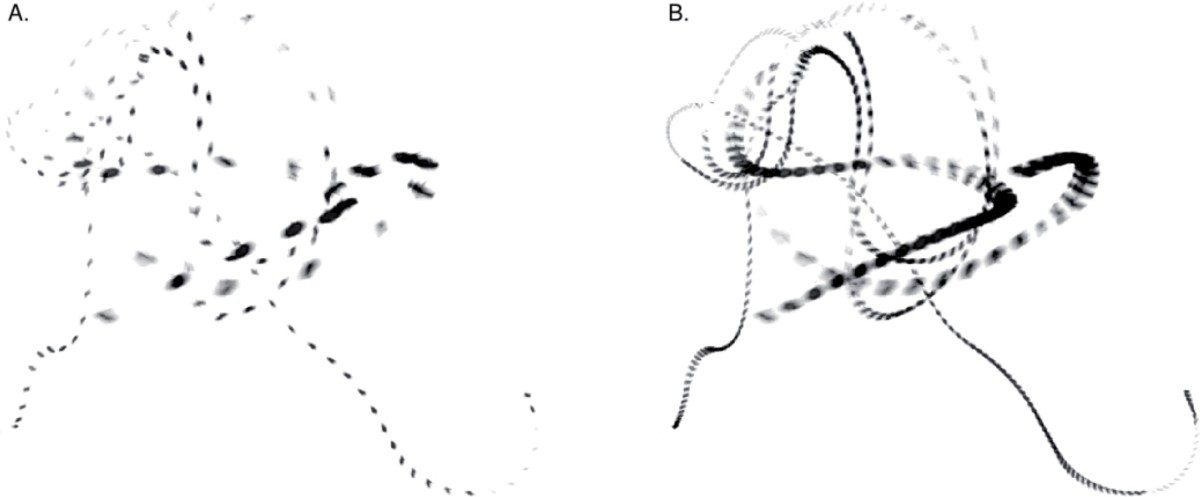

And why does this matter to birds? Because if they need to pluck a super-fast fly from the air, while flying, they had better be able to see it clearly.

And fast-flying birds need to respond to lots of other things – as they fly through trees that might be blowing in the wind, they need to see small branches sway or appear in their flight path, and they need to quickly adjust their flight accordingly. Their life depends on it.

View an online video of what a flying insect looks like to a bird with ultra-rapid vision.

References

Boström, J. E., M. Dimitrova, C. Canton, O. Håstad, A. Qvarnström, and A. Ödeen (2016). Ultra-Rapid Vision in Birds. PLOS One 11:e0151099-e0151099

Jack Dumbacher is on the Golden Gate Bird Alliance Board of Directors and chairs its San Francisco Conservation Committee. Chair of the Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy at California Academy of Sciences, Jack is author of more than two dozen scholarly articles on birds. Together with Bob Lewis and Eddie Bartley, Jack teaches the year-long Master Birder class co-sponsored by GGBA and Cal Academy.