Farallon Islands through the centuries

Editor’s Note: The Farallon Islands have been part of Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s history since our founding a century ago in 1917. Today they face a new threat as the Trump Administration considers paring back the surrounding National Marine Sanctuary to allow oil drilling. This is a reprint of a story that ran in The Gull newsletter ten years ago as part of our 90th anniversary celebrations.

By Harry Fuller

Golden Gate Bird Alliance began as nature’s presence was at a low ebb on the Farallon Islands. Until European explorers came, the 211 acres of scattered rocky islands were the undisturbed home of a dense population of seabirds, marine mammals, and flying invertebrates.

By 1917, when the Audubon Association of the Pacific (as GGBA was initially called) was formed, the nesting bird populations were greatly reduced. Some mammals native to the Farallones had disappeared completely. What happened?

Early Native Americans feared the islands and stayed away. The first humans to set foot deliberately on the Farallones may have been Sir Francis Drake’s crew. In 1579 his men hunted sea lions and collected seabird eggs, beginning a pattern of exploitation that would last for 400 years.

Sailing merchants wanted Northern Fur Seal pelts to trade in China. By 1810 hunters lived seasonally on the islands. That year, 30,000 fur seal hides were collected during a five-month season. In 1817 a permanent Russian hunting colony was established on Southeast Farallon Island. The highest fur seal kill—200,000—was probably 1834. Seabird eggs and seabird meat were collected and shipped north to the Russian post at Fort Ross. In 1828 approximately 50,000 Farallones seabirds were killed for food. The Russians left in 1841, just before the most profitable exploitation of the islands’ wildlife.

After the Gold Rush, fresh eggs were in demand. California had no poultry industry so commercial egging struck the Farallon Islands. In 1854 over half a million seabird eggs were gathered for sale to San Francisco restaurants. Only the Western Gull eggs were avoided as their thin shells would not survive the ocean passage. Some eggers also avoided disturbing the nests of Tufted Puffins because of the birds’ ferocious bite. Common Murre, all cormorant species, and other birds that nested in the open were easy targets.

Compounding the damage to wildlife was the construction of the first lighthouse, begun in 1852. That brought permanent residents with pets, goats, and, worst of all, Australian hares that were freed on the island. The habitat rapidly disintegrated, the fur seals and elephant seals were wiped out, and even sea lions and harbor seals were at a low number by the end of the 19th century. Seabird populations were extirpated or left with tiny colonies. Even the nesting ravens on Southeast Farallon had been shot. In 1896, the last year of commercial egging on the islands, only 100,000 eggs could be found. Yet residents continued to gather eggs until 1905.

The earliest conservation efforts to protect the Farallones had been led by the California Academy of Sciences, but the arrival of the Audubon Association coincided with one of the worst threats ever to face Farallon seabirds.

The spread of automobiles increased the oceanic transport of petroleum. Before entering San Francisco Bay, tankers would empty their ballast tanks in the vicinity of the Farallon Islands. Currents brought the slick of waste oil to the islands, where it covered the shores and killed many of the remaining seabirds and mammals. Concerned lighthouse officials contacted the fledgling association.

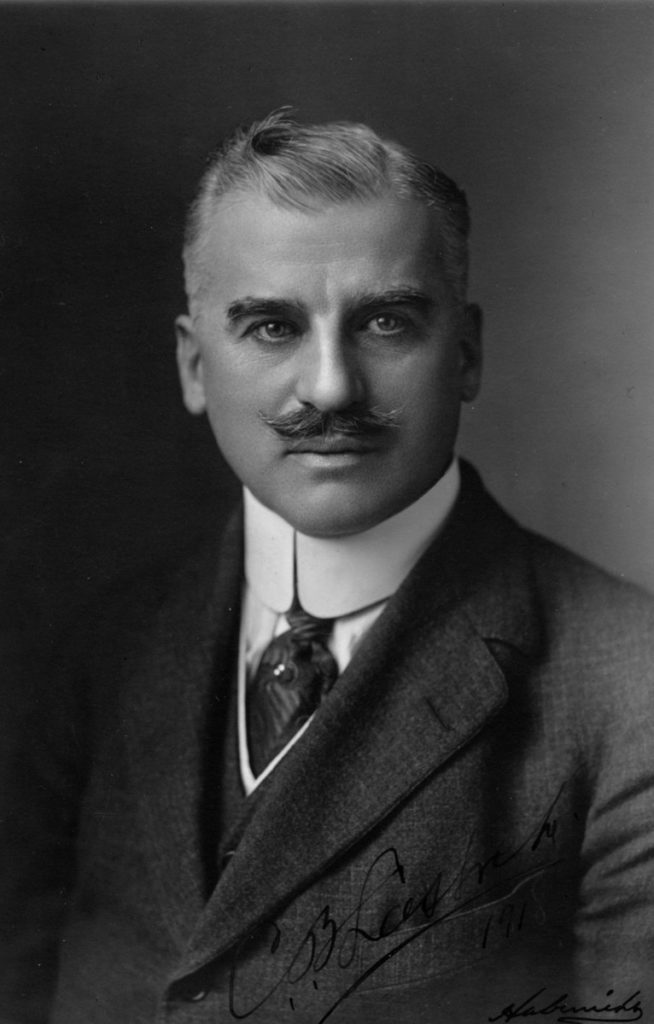

In a letter dated March 21, 1917, Inspector H. W. Rhodes of the 18th Lighthouse District, wrote to Carlos B. Lastreto, the Audubon Association’s first president:

“The keeper of the Farallon Light Station has reported that in his opinion if vessels are not prohibited from pumping overboard crude oil with their water ballast in the vicinity of the Farallon Islands, all diving birds of the island, such as murres, will disappear. He further states that during the last nesting season all of the birds from some of the rookeries were killed, most of them dying on the rocks after being saturated with oil. This loss is not confined to the nesting season, as many of the birds remaining on the island have died from the same cause during the past winter.”

The association was less than three months old, but it was ready to embark on its first serious effort at conservation. Lastreto and Dr. Barton Evermann, a prominent ichthyologist and director of the California Academy of Sciences, worked as a committee of two, trying to curb the dumping of waste oil. Evermann was also president of the Cooper Ornithological Club at that time. In 1917 the U.S. territorial limit was only three miles out from shore. so there was no hope of government intervention in stopping ships from dumping oil 20 miles or more out to sea.

The committee got support from the California Fish and Game Department, the Pacific Fisheries Society, and the Cooper Ornithological Club. They did convince the major oil companies along the Pacific Coast to begin recycling waste oil at onshore facilities, instead of dumping at sea. Lastreto also conducted a survey of harbors around the Pacific to find if oil dumping was a widespread problem. These actions were a crucial early step in protecting the Farallones and were probably among the first organized conservation efforts to stop oil dumping at sea.

Once oil dumping was reduced, other problems such as gill-netting and overfishing continued to damage Farallon wildlife. According to a report in the August 1930 Gull, a field trip to the Farallones held a shocking disappointment for the association members who went: Only four Common Murres could be found. Western Gulls were abundant, and the only land birds were Rock Wren and House Sparrow.

Bird populations were slow to recover in the mid-20th century. By 1959 the Common Murre population was still only 6,000 breeding birds. Until the recent effects of climate change, there were a series of optimistic milestones: Rhinoceros Auklets resumed breeding in 1972 and elephant seals in 1973. The last feral rabbit was killed in 1975.

By 1980 there were around 60,000 Common Murres breeding on the islands. In 1996 the first Northern Fur Seal was born on the islands after the species had been extirpated, and 10 years later there were 80 pups. By January 2007, the elephant seal colony already boasted over 70 pups for the current breeding season….

Editor’s Update: Today the Farallon Islands remain critically important yet vulnerable habitat.

They now host the largest seabird breeding colony in the United States outside of Alaska and Hawaii. Twenty-five percent of California’s breeding seabirds, with more than 300,000 individuals of 13 species, can be found there. They provide breeding grounds for about fifty percent of the world’s population of Ashy Storm-Petrels, listed as a Species of Management Concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Yet breeding success fluctuates from year to year. Point Blue, which monitors bird populations on the Farallones, reports that:

In general, the number of birds attempting to breed and their breeding success were both lower during 2016 relative to recent years. Chicks generally grew slowly and fledged at lower weights when compared to more productive seasons.

Warm water from a strong El Niño and the continued presence of “the blob” in the northeast Pacific contributed to lower overall ocean productivity and consequently poor breeding success.

During 2016, breeding populations decreased for all species except Double-crested and Pelagic cormorants, Common Murre, and Tufted Puffin, when compared to 2015. After recording the lowest Western Gull breeding population observed during our time series during 2015, this population further declined during 2016. Brandt’s Cormorants, California Gulls, Pigeon Guillemots, and Cassin’s Auklets also exhibited large declines relative to last season. Black Oystercatchers had the lowest breeding population in our time series, equal to last year. In contrast, Tufted Puffins continued to increase, establishing a new high count for the fourth consecutive year.

Reproductive success was lower for most species in 2016 when compared to 2015, including complete breeding failure for Pelagic Cormorants and the lowest success for Pigeon Guillemots in 10 years. Rhinoceros Auklets were the only species to have higher success relative to last season while Cassin’s Auklet success was equal to 2015.

Juvenile rockfish (Sebastes spp.) remained the dominant component of chick diet for Rhinoceros Auklets and Pigeon Guillemots, though they were less abundant than last season, while Anchovies were the dominant prey item for murres. Krill seemed to be available for Cassin’s auklets throughout the season, allowing for high breeding success and even a few successful second broods – the first observed in 3 years.

Given both the importance and the vulnerability of the Farallones breeding site, it is completely irresponsible even to consider opening the surrounding Northern California waters to oil drilling.

The Trump Administration is currently considering whether to reduce/eliminate eleven National Marine Sanctuaries, including the Greater Farallones sanctuary and three others off the California coast. It is also considering opening California coastal waters to offshore drilling over the next five years.

Please take action by sending an email against offshore drilling to the Interior Department and ins support of the National Marine Sanctuaries to the Commerce Department. Click here to read our recent Action Alert with links to send emails. Or go straight to emailing each agency:

The deadline for filing comments on the marine sanctuaries is August 14, 2017.

Harry Fuller, a former field trip leader with Golden Gate Bird Alliance, now lives in Southern Oregon. He will be leading a birding tour of Southern Oregon for GGBA on Memorial Day weekend in 2018: See our Travel with GGBA page for details after August 21, when our 2018 Travel line-up will be posted. Harry is the author of several books including Freeway Birding: San Francisco to Seattle and Great Gray Owl of California, Oregon, and Washington.