Blackbird fly! (off of my horse trailer)

By Eric Schroeder

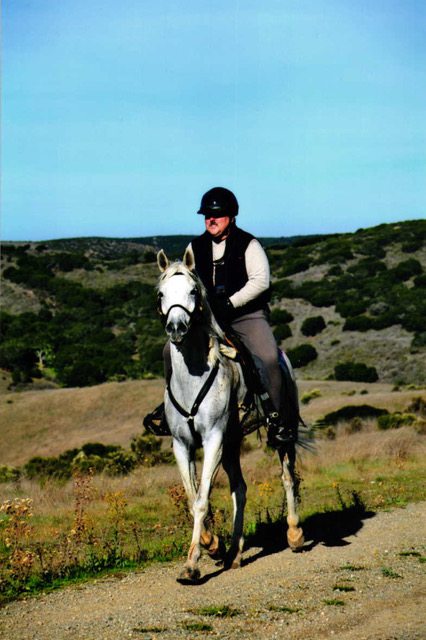

As a horse owner dependent upon a trailer to get into our local parks in the spring, I am vigilant about the trailer’s readiness. My trailer lives at Hossmoor, a 138-acre horse property where I’ve seen over fifty species of birds. It’s also just an eight-minute drive from Briones Regional Park—an excellent place to ride and to bird year-round.

But this spring my horse had been injured and I let down my guard. Walking by the trailer in April,, I noticed that what we trailer owners fear most had happened—a Brewer’s Blackbird was sitting on a nest she had built on the spare battery compartment under the gooseneck of my trailer.

I thought to myself that if she hadn’t yet laid any eggs, I could remove the nest—maybe put it on somebody else’s trailer that wasn’t in use. I approached, the bird flew the nest, and I poked my head in. Four eggs.

Why my trailer? There were 25 other trailers that bird could have chosen! I realized immediately I wouldn’t be using the trailer for a while, even when my horse was sound again. But just how long would that be? On the west coast where Brewer’s Blackbirds are non-migratory, they start pairing up as early as the third week in January and all birds are paired by the second week in February. (I realize now that I should have been checking my trailer earlier—and regularly!—since females built the nests over a nine-day period.)

Generally, eastern populations of Brewer’s Blackbirds tend to nest on the ground, while western populations built nests in a wide variety of locations—in bushes, in vegetation over water, in vegetable crops, and on available trailer perches. Nests built above ground tend to be built from twigs and weed stems with the rougher outer construction giving way to finer materials around the bowl. Bowls are often lined with horsehair—lots of that where my blackbirds live!

Brewer’s Blackbirds are synchronous nesters, meaning that nest building for an entire colony starts at the same time. (If I had been paying closer attention to the blackbirds as a whole population, this wouldn’t have happened!) I discovered the eggs in early April but I didn’t have any idea how long they had been there (or when I might use my trailer again). Females generally lay up to five eggs and deposit an egg a day until the clutch is complete. The four in the nest were soon hatched—the average incubation time turns out to be 12–13 days. The male bird didn’t help with incubation (and apparently males don’t help with nest building either), but he was on guard at a nearby perch on another trailer, watching the female closely and sometimes driving off other males.

So once the chicks were hatched, the only thing keeping me from getting my trailer back was the time it would take them to fledge. Brewer’s Blackbirds are altricial, meaning that they are helpless at birth. Hatchlings are nearly naked and poorly coordinated, but within 2–3 minutes of hatching, they are able to open their mouths for food, and within 2-3 hours they are peeping and demanding it. Luckily, nestlings mature quickly and the birds fledge in 12–16 days. (Birds that are disturbed by humans can leave as early as nine days after hatching, but I didn’t think it would be playing fair to evict the young blackbirds on such short notice.) When I would walk by the trailer, I would find myself humming the chorus of the Beatles’ song “Blackbird”—“Blackbird fly, blackbird fly!

Then one day I was talking to another boarder who was giving her horse a bath when a Brewer’s fledgling dropped at my feet. My companion looked up and said, “That’s the second one today.” There was a nest just under the roof of the wash rack (remember what I said earlier about where these birds nest!) and apparently the chicks had begun vacating the premises.

I looked at this fledgling closely. It was pretty ugly. But then I thought, “You beauty!” since I realized that “synchronous nesting” must imply “synchronous fledging.” I hurried over to my trailer and discovered that the chicks had already flown the coop. I noticed an adult bird nearby with a fledgling and wondered if those were from my nest: Parents and their offspring spend up to three weeks near the nest site, with the parents continuing to feed the young as they learn to fend for themselves. And one to two weeks after fledging, several family groups will form a flock that remains in the vicinity as the young become independent.

Over the next week I noticed lots of fledging blackbirds—both Brewer’s and Red-wings. (Contra Costa county has large populations of both species and at Hossmoor I often see large mixed flocks.) I thought to myself that all was well now, though I was momentarily chastened by something I had read—that in coastal California a second brood is possible since resident Brewer’s Blackbirds pair up so early in the season!

But then I relaxed as I also recalled that birds that have second clutches don’t reuse nests. It was without guilt, then, that I was able to add the nest to my small but growing collection of bird homes, thinking that possession of the nest was a reasonable rent to collect for a season of successful reproduction.

Source material for this piece is from “Brewer’s Blackbird” by Stephen G. Martin, in Birds of North America online, 2012.

Eric Schroeder is a retired UC Davis lecturer and administrator who still leads month-long Summer Abroad student program for UCD in South Africa and Australia. He enjoys viewing wildlife in the sky, on land, and under the sea. He’s a recent graduate of the Master Birding Program jointly sponsored by the Golden Gate Bird Alliance and the California Academy of Sciences. He has previously written for Golden Gate Birder on Bewick’s Wrens and on his first experience with Birdathon.